Sound Effects—Let’s Not Hear It for UAM!

Some noises, we know, are joyful: Laughter. Music. A crackling fireplace. Other sounds are grating (some, intentionally so): a siren, nails on a chalkboard, an electric drill.

For all the technical challenges the UAM industry faces in gaining acceptance for eVTOLs, one of the top challenges, according to a 2019 NASA UAM study, is building aircraft that emit noise at levels acceptable to the communities-at-large where eVTOLs hope to operate on a commercially viable schedule.

Like much of UAM development, noise abatement—successful noise abatement—is, and needs to be, a collaborative effort. Manufacturers, government and community leaders, researchers, regulators, and airport (and ultimately, vertiport) operators are doing just that.

Listen Up

When it comes to noise, even size doesn’t matter. A buzzing fly can be just as bothersome as a Boeing Apache or a Bell Viper overhead. The flying public doesn’t call them “choppers” out of affection.

While the industry dreams of thousands of eVTOLs transporting millions of satisfied customers from Point A to Point B, others envision a noise nightmare—swarms of small aircraft disturbing their peace.

According to David Josephson, a Santa Cruz, California-based acoustics and noise advisor, “The physics of sound, the physiology of sound perception in the brain, and our experience with noise events” all combine to form our opinion whether a noise is acceptable or objectionable.

Consequently, UAM hopefuls are using existing helicopter acoustic signatures, simulators, and experimental helipads to develop a better understanding of the physics of vertical lift acoustics. They’re studying what happens while executing moves in the sky, such as turning, climb or descent rates, or making trim changes.

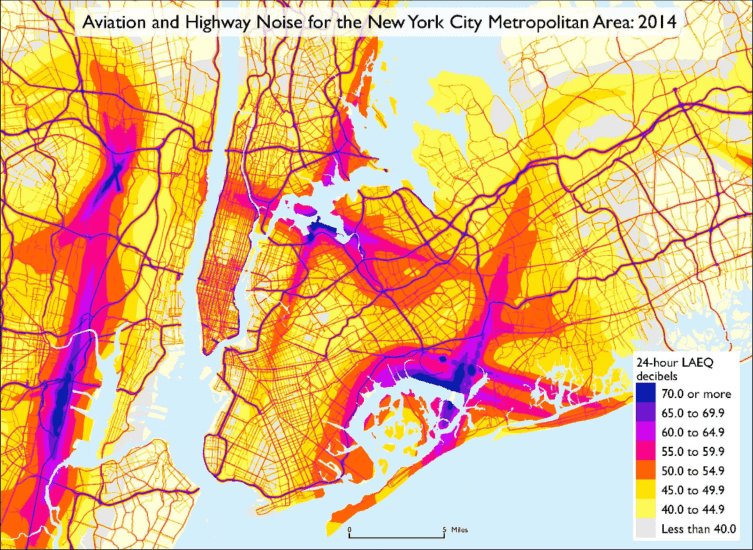

The effects of ambient conditions are also being considered. Cliff Johnson, a research engineer and project lead at the FAA’s Tech Center, is working with industry leaders to understand the impact UAM will have on air traffic control. They are working to understand how routes can be optimized and what constitutes “flying neighborly” in the public’s view.

Daily noise assessments may not be adequate. UAM may require hourly assessments given how ubiquitous these flights hope to be.

Getting UAM Off the Ground

Rohit Goyal, with Uber Elevate operations, describes five major pillars underpinning the research initiatives: multimodal aerial ridesharing, automated platforms, the industry ecosystem (including USAF), electric skyports, and connected skyports.

The developers want to understand how people react to ambient noise, operational noise, and their overall perceptions of eVTOL noise—not just what you hear, but what you see and feel too.

Initial system goals include flight speeds up to 150 mph, loads that accommodate four passengers and a pilot, a range of 60 miles, noise at least 1.5 decibels quieter than helicopters, and reliability of the aircraft to fly at least 2,000 hours per year.

Land use compatibility is critical too, says Goyal. Does land use compatibility limit daily operations? Does higher ambient noise allow for higher operational noise?

When aircraft first took to the skies in 1903, the public was astonished by the opportunities and the accomplishment of humans being able to take flight. Once the initial wonder wore off, the questions and concerns about safety, noise, traffic, and costs soon followed. But, if the past is prologue, the future is bright. “Your greatness is measured by your horizons,” said Michelangelo.

Want to continue to stay up-to-date about the latest developments in the eVTOL industry? Subscribe to AeroCar Journal now. It’s FREE (for a limited time)!

Join us on Twitter for the latest news, analysis, and insight in the eVTOL industry. AeroCarJ